For the past several decades, and especially since the Six-Day War in 1967, the centrepiece of US Middle Eastern policy has been its relationship with Israel. The combination of unwavering support for Israel and the related effort to spread ‘democracy’ throughout the region has inflamed Arab and Islamic opinion and jeopardised not only US security but that of much of the rest of the world. This situation has no equal in American political history. Why has the US been willing to set aside its own security and that of many of its allies in order to advance the interests of another state? One might assume that the bond between the two countries was based on shared strategic interests or compelling moral imperatives, but neither explanation can account for the remarkable level of material and diplomatic support that the US provides.

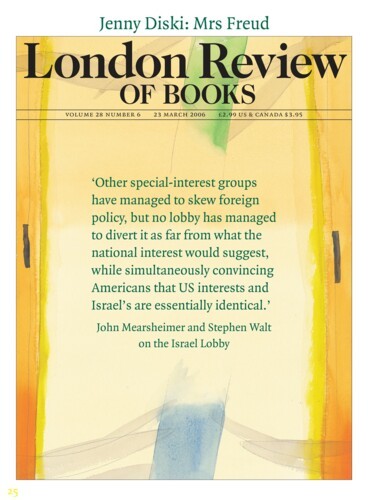

Instead, the thrust of US policy in the region derives almost entirely from domestic politics, and especially the activities of the ‘Israel Lobby’. Other special-interest groups have managed to skew foreign policy, but no lobby has managed to divert it as far from what the national interest would suggest, while simultaneously convincing Americans that US interests and those of the other country – in this case, Israel – are essentially identical.

Since the October War in 1973, Washington has provided Israel with a level of support dwarfing that given to any other state. It has been the largest annual recipient of direct economic and military assistance since 1976, and is the largest recipient in total since World War Two, to the tune of well over $140 billion (in 2004 dollars). Israel receives about $3 billion in direct assistance each year, roughly one-fifth of the foreign aid budget, and worth about $500 a year for every Israeli. This largesse is especially striking since Israel is now a wealthy industrial state with a per capita income roughly equal to that of South Korea or Spain.

Other recipients get their money in quarterly installments, but Israel receives its entire appropriation at the beginning of each fiscal year and can thus earn interest on it. Most recipients of aid given for military purposes are required to spend all of it in the US, but Israel is allowed to use roughly 25 per cent of its allocation to subsidise its own defence industry. It is the only recipient that does not have to account for how the aid is spent, which makes it virtually impossible to prevent the money from being used for purposes the US opposes, such as building settlements on the West Bank. Moreover, the US has provided Israel with nearly $3 billion to develop weapons systems, and given it access to such top-drawer weaponry as Blackhawk helicopters and F-16 jets. Finally, the US gives Israel access to intelligence it denies to its Nato allies and has turned a blind eye to Israel’s acquisition of nuclear weapons.

Washington also provides Israel with consistent diplomatic support. Since 1982, the US has vetoed 32 Security Council resolutions critical of Israel, more than the total number of vetoes cast by all the other Security Council members. It blocks the efforts of Arab states to put Israel’s nuclear arsenal on the IAEA’s agenda. The US comes to the rescue in wartime and takes Israel’s side when negotiating peace. The Nixon administration protected it from the threat of Soviet intervention and resupplied it during the October War. Washington was deeply involved in the negotiations that ended that war, as well as in the lengthy ‘step-by-step’ process that followed, just as it played a key role in the negotiations that preceded and followed the 1993 Oslo Accords. In each case there was occasional friction between US and Israeli officials, but the US consistently supported the Israeli position. One American participant at Camp David in 2000 later said: ‘Far too often, we functioned … as Israel’s lawyer.’ Finally, the Bush administration’s ambition to transform the Middle East is at least partly aimed at improving Israel’s strategic situation.

This extraordinary generosity might be understandable if Israel were a vital strategic asset or if there were a compelling moral case for US backing. But neither explanation is convincing. One might argue that Israel was an asset during the Cold War. By serving as America’s proxy after 1967, it helped contain Soviet expansion in the region and inflicted humiliating defeats on Soviet clients like Egypt and Syria. It occasionally helped protect other US allies (like King Hussein of Jordan) and its military prowess forced Moscow to spend more on backing its own client states. It also provided useful intelligence about Soviet capabilities.

Backing Israel was not cheap, however, and it complicated America’s relations with the Arab world. For example, the decision to give $2.2 billion in emergency military aid during the October War triggered an Opec oil embargo that inflicted considerable damage on Western economies. For all that, Israel’s armed forces were not in a position to protect US interests in the region. The US could not, for example, rely on Israel when the Iranian Revolution in 1979 raised concerns about the security of oil supplies, and had to create its own Rapid Deployment Force instead.

The first Gulf War revealed the extent to which Israel was becoming a strategic burden. The US could not use Israeli bases without rupturing the anti-Iraq coalition, and had to divert resources (e.g. Patriot missile batteries) to prevent Tel Aviv doing anything that might harm the alliance against Saddam Hussein. History repeated itself in 2003: although Israel was eager for the US to attack Iraq, Bush could not ask it to help without triggering Arab opposition. So Israel stayed on the sidelines once again.

Beginning in the 1990s, and even more after 9/11, US support has been justified by the claim that both states are threatened by terrorist groups originating in the Arab and Muslim world, and by ‘rogue states’ that back these groups and seek weapons of mass destruction. This is taken to mean not only that Washington should give Israel a free hand in dealing with the Palestinians and not press it to make concessions until all Palestinian terrorists are imprisoned or dead, but that the US should go after countries like Iran and Syria. Israel is thus seen as a crucial ally in the war on terror, because its enemies are America’s enemies. In fact, Israel is a liability in the war on terror and the broader effort to deal with rogue states.

‘Terrorism’ is not a single adversary, but a tactic employed by a wide array of political groups. The terrorist organisations that threaten Israel do not threaten the United States, except when it intervenes against them (as in Lebanon in 1982). Moreover, Palestinian terrorism is not random violence directed against Israel or ‘the West’; it is largely a response to Israel’s prolonged campaign to colonise the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

More important, saying that Israel and the US are united by a shared terrorist threat has the causal relationship backwards: the US has a terrorism problem in good part because it is so closely allied with Israel, not the other way around. Support for Israel is not the only source of anti-American terrorism, but it is an important one, and it makes winning the war on terror more difficult. There is no question that many al-Qaida leaders, including Osama bin Laden, are motivated by Israel’s presence in Jerusalem and the plight of the Palestinians. Unconditional support for Israel makes it easier for extremists to rally popular support and to attract recruits.

As for so-called rogue states in the Middle East, they are not a dire threat to vital US interests, except inasmuch as they are a threat to Israel. Even if these states acquire nuclear weapons – which is obviously undesirable – neither America nor Israel could be blackmailed, because the blackmailer could not carry out the threat without suffering overwhelming retaliation. The danger of a nuclear handover to terrorists is equally remote, because a rogue state could not be sure the transfer would go undetected or that it would not be blamed and punished afterwards. The relationship with Israel actually makes it harder for the US to deal with these states. Israel’s nuclear arsenal is one reason some of its neighbours want nuclear weapons, and threatening them with regime change merely increases that desire.

A final reason to question Israel’s strategic value is that it does not behave like a loyal ally. Israeli officials frequently ignore US requests and renege on promises (including pledges to stop building settlements and to refrain from ‘targeted assassinations’ of Palestinian leaders). Israel has provided sensitive military technology to potential rivals like China, in what the State Department inspector-general called ‘a systematic and growing pattern of unauthorised transfers’. According to the General Accounting Office, Israel also ‘conducts the most aggressive espionage operations against the US of any ally’. In addition to the case of Jonathan Pollard, who gave Israel large quantities of classified material in the early 1980s (which it reportedly passed on to the Soviet Union in return for more exit visas for Soviet Jews), a new controversy erupted in 2004 when it was revealed that a key Pentagon official called Larry Franklin had passed classified information to an Israeli diplomat. Israel is hardly the only country that spies on the US, but its willingness to spy on its principal patron casts further doubt on its strategic value.

Israel’s strategic value isn’t the only issue. Its backers also argue that it deserves unqualified support because it is weak and surrounded by enemies; it is a democracy; the Jewish people have suffered from past crimes and therefore deserve special treatment; and Israel’s conduct has been morally superior to that of its adversaries. On close inspection, none of these arguments is persuasive. There is a strong moral case for supporting Israel’s existence, but that is not in jeopardy. Viewed objectively, its past and present conduct offers no moral basis for privileging it over the Palestinians.

Israel is often portrayed as David confronted by Goliath, but the converse is closer to the truth. Contrary to popular belief, the Zionists had larger, better equipped and better led forces during the 1947-49 War of Independence, and the Israel Defence Forces won quick and easy victories against Egypt in 1956 and against Egypt, Jordan and Syria in 1967 – all of this before large-scale US aid began flowing. Today, Israel is the strongest military power in the Middle East. Its conventional forces are far superior to those of its neighbours and it is the only state in the region with nuclear weapons. Egypt and Jordan have signed peace treaties with it, and Saudi Arabia has offered to do so. Syria has lost its Soviet patron, Iraq has been devastated by three disastrous wars and Iran is hundreds of miles away. The Palestinians barely have an effective police force, let alone an army that could pose a threat to Israel. According to a 2005 assessment by Tel Aviv University’s Jaffee Centre for Strategic Studies, ‘the strategic balance decidedly favours Israel, which has continued to widen the qualitative gap between its own military capability and deterrence powers and those of its neighbours.’ If backing the underdog were a compelling motive, the United States would be supporting Israel’s opponents.

That Israel is a fellow democracy surrounded by hostile dictatorships cannot account for the current level of aid: there are many democracies around the world, but none receives the same lavish support. The US has overthrown democratic governments in the past and supported dictators when this was thought to advance its interests – it has good relations with a number of dictatorships today.

Some aspects of Israeli democracy are at odds with core American values. Unlike the US, where people are supposed to enjoy equal rights irrespective of race, religion or ethnicity, Israel was explicitly founded as a Jewish state and citizenship is based on the principle of blood kinship. Given this, it is not surprising that its 1.3 million Arabs are treated as second-class citizens, or that a recent Israeli government commission found that Israel behaves in a ‘neglectful and discriminatory’ manner towards them. Its democratic status is also undermined by its refusal to grant the Palestinians a viable state of their own or full political rights.

A third justification is the history of Jewish suffering in the Christian West, especially during the Holocaust. Because Jews were persecuted for centuries and could feel safe only in a Jewish homeland, many people now believe that Israel deserves special treatment from the United States. The country’s creation was undoubtedly an appropriate response to the long record of crimes against Jews, but it also brought about fresh crimes against a largely innocent third party: the Palestinians.

This was well understood by Israel’s early leaders. David Ben-Gurion told Nahum Goldmann, the president of the World Jewish Congress:

If I were an Arab leader I would never make terms with Israel. That is natural: we have taken their country … We come from Israel, but two thousand years ago, and what is that to them? There has been anti-semitism, the Nazis, Hitler, Auschwitz, but was that their fault? They only see one thing: we have come here and stolen their country. Why should they accept that?

Since then, Israeli leaders have repeatedly sought to deny the Palestinians’ national ambitions. When she was prime minister, Golda Meir famously remarked that ‘there is no such thing as a Palestinian.’ Pressure from extremist violence and Palestinian population growth has forced subsequent Israeli leaders to disengage from the Gaza Strip and consider other territorial compromises, but not even Yitzhak Rabin was willing to offer the Palestinians a viable state. Ehud Barak’s purportedly generous offer at Camp David would have given them only a disarmed set of Bantustans under de facto Israeli control. The tragic history of the Jewish people does not obligate the US to help Israel today no matter what it does.

Israel’s backers also portray it as a country that has sought peace at every turn and shown great restraint even when provoked. The Arabs, by contrast, are said to have acted with great wickedness. Yet on the ground, Israel’s record is not distinguishable from that of its opponents. Ben-Gurion acknowledged that the early Zionists were far from benevolent towards the Palestinian Arabs, who resisted their encroachments – which is hardly surprising, given that the Zionists were trying to create their own state on Arab land. In the same way, the creation of Israel in 1947-48 involved acts of ethnic cleansing, including executions, massacres and rapes by Jews, and Israel’s subsequent conduct has often been brutal, belying any claim to moral superiority. Between 1949 and 1956, for example, Israeli security forces killed between 2700 and 5000 Arab infiltrators, the overwhelming majority of them unarmed. The IDF murdered hundreds of Egyptian prisoners of war in both the 1956 and 1967 wars, while in 1967, it expelled between 100,000 and 260,000 Palestinians from the newly conquered West Bank, and drove 80,000 Syrians from the Golan Heights.

During the first intifada, the IDF distributed truncheons to its troops and encouraged them to break the bones of Palestinian protesters. The Swedish branch of Save the Children estimated that ‘23,600 to 29,900 children required medical treatment for their beating injuries in the first two years of the intifada.’ Nearly a third of them were aged ten or under. The response to the second intifada has been even more violent, leading Ha’aretz to declare that ‘the IDF … is turning into a killing machine whose efficiency is awe-inspiring, yet shocking.’ The IDF fired one million bullets in the first days of the uprising. Since then, for every Israeli lost, Israel has killed 3.4 Palestinians, the majority of whom have been innocent bystanders; the ratio of Palestinian to Israeli children killed is even higher (5.7:1). It is also worth bearing in mind that the Zionists relied on terrorist bombs to drive the British from Palestine, and that Yitzhak Shamir, once a terrorist and later prime minister, declared that ‘neither Jewish ethics nor Jewish tradition can disqualify terrorism as a means of combat.’

The Palestinian resort to terrorism is wrong but it isn’t surprising. The Palestinians believe they have no other way to force Israeli concessions. As Ehud Barak once admitted, had he been born a Palestinian, he ‘would have joined a terrorist organisation’.

So if neither strategic nor moral arguments can account for America’s support for Israel, how are we to explain it?

The explanation is the unmatched power of the Israel Lobby. We use ‘the Lobby’ as shorthand for the loose coalition of individuals and organisations who actively work to steer US foreign policy in a pro-Israel direction. This is not meant to suggest that ‘the Lobby’ is a unified movement with a central leadership, or that individuals within it do not disagree on certain issues. Not all Jewish Americans are part of the Lobby, because Israel is not a salient issue for many of them. In a 2004 survey, for example, roughly 36 per cent of American Jews said they were either ‘not very’ or ‘not at all’ emotionally attached to Israel.

Jewish Americans also differ on specific Israeli policies. Many of the key organisations in the Lobby, such as the American-Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) and the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organisations, are run by hardliners who generally support the Likud Party’s expansionist policies, including its hostility to the Oslo peace process. The bulk of US Jewry, meanwhile, is more inclined to make concessions to the Palestinians, and a few groups – such as Jewish Voice for Peace – strongly advocate such steps. Despite these differences, moderates and hardliners both favour giving steadfast support to Israel.

Not surprisingly, American Jewish leaders often consult Israeli officials, to make sure that their actions advance Israeli goals. As one activist from a major Jewish organisation wrote, ‘it is routine for us to say: “This is our policy on a certain issue, but we must check what the Israelis think.” We as a community do it all the time.’ There is a strong prejudice against criticising Israeli policy, and putting pressure on Israel is considered out of order. Edgar Bronfman Sr, the president of the World Jewish Congress, was accused of ‘perfidy’ when he wrote a letter to President Bush in mid-2003 urging him to persuade Israel to curb construction of its controversial ‘security fence’. His critics said that ‘it would be obscene at any time for the president of the World Jewish Congress to lobby the president of the United States to resist policies being promoted by the government of Israel.’

Similarly, when the president of the Israel Policy Forum, Seymour Reich, advised Condoleezza Rice in November 2005 to ask Israel to reopen a critical border crossing in the Gaza Strip, his action was denounced as ‘irresponsible’: ‘There is,’ his critics said, ‘absolutely no room in the Jewish mainstream for actively canvassing against the security-related policies … of Israel.’ Recoiling from these attacks, Reich announced that ‘the word “pressure” is not in my vocabulary when it comes to Israel.’

Jewish Americans have set up an impressive array of organisations to influence American foreign policy, of which AIPAC is the most powerful and best known. In 1997, Fortune magazine asked members of Congress and their staffs to list the most powerful lobbies in Washington. AIPAC was ranked second behind the American Association of Retired People, but ahead of the AFL-CIO and the National Rifle Association. A National Journal study in March 2005 reached a similar conclusion, placing AIPAC in second place (tied with AARP) in the Washington ‘muscle rankings’.

The Lobby also includes prominent Christian evangelicals like Gary Bauer, Jerry Falwell, Ralph Reed and Pat Robertson, as well as Dick Armey and Tom DeLay, former majority leaders in the House of Representatives, all of whom believe Israel’s rebirth is the fulfilment of biblical prophecy and support its expansionist agenda; to do otherwise, they believe, would be contrary to God’s will. Neo-conservative gentiles such as John Bolton; Robert Bartley, the former Wall Street Journal editor; William Bennett, the former secretary of education; Jeane Kirkpatrick, the former UN ambassador; and the influential columnist George Will are also steadfast supporters.

The US form of government offers activists many ways of influencing the policy process. Interest groups can lobby elected representatives and members of the executive branch, make campaign contributions, vote in elections, try to mould public opinion etc. They enjoy a disproportionate amount of influence when they are committed to an issue to which the bulk of the population is indifferent. Policymakers will tend to accommodate those who care about the issue, even if their numbers are small, confident that the rest of the population will not penalise them for doing so.

In its basic operations, the Israel Lobby is no different from the farm lobby, steel or textile workers’ unions, or other ethnic lobbies. There is nothing improper about American Jews and their Christian allies attempting to sway US policy: the Lobby’s activities are not a conspiracy of the sort depicted in tracts like the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. For the most part, the individuals and groups that comprise it are only doing what other special interest groups do, but doing it very much better. By contrast, pro-Arab interest groups, in so far as they exist at all, are weak, which makes the Israel Lobby’s task even easier.

The Lobby pursues two broad strategies. First, it wields its significant influence in Washington, pressuring both Congress and the executive branch. Whatever an individual lawmaker or policymaker’s own views may be, the Lobby tries to make supporting Israel the ‘smart’ choice. Second, it strives to ensure that public discourse portrays Israel in a positive light, by repeating myths about its founding and by promoting its point of view in policy debates. The goal is to prevent critical comments from getting a fair hearing in the political arena. Controlling the debate is essential to guaranteeing US support, because a candid discussion of US-Israeli relations might lead Americans to favour a different policy.

A key pillar of the Lobby’s effectiveness is its influence in Congress, where Israel is virtually immune from criticism. This in itself is remarkable, because Congress rarely shies away from contentious issues. Where Israel is concerned, however, potential critics fall silent. One reason is that some key members are Christian Zionists like Dick Armey, who said in September 2002: ‘My No. 1 priority in foreign policy is to protect Israel.’ One might think that the No. 1 priority for any congressman would be to protect America. There are also Jewish senators and congressmen who work to ensure that US foreign policy supports Israel’s interests.

Another source of the Lobby’s power is its use of pro-Israel congressional staffers. As Morris Amitay, a former head of AIPAC, once admitted, ‘there are a lot of guys at the working level up here’ – on Capitol Hill – ‘who happen to be Jewish, who are willing … to look at certain issues in terms of their Jewishness … These are all guys who are in a position to make the decision in these areas for those senators … You can get an awful lot done just at the staff level.’

AIPAC itself, however, forms the core of the Lobby’s influence in Congress. Its success is due to its ability to reward legislators and congressional candidates who support its agenda, and to punish those who challenge it. Money is critical to US elections (as the scandal over the lobbyist Jack Abramoff’s shady dealings reminds us), and AIPAC makes sure that its friends get strong financial support from the many pro-Israel political action committees. Anyone who is seen as hostile to Israel can be sure that AIPAC will direct campaign contributions to his or her political opponents. AIPAC also organises letter-writing campaigns and encourages newspaper editors to endorse pro-Israel candidates.

There is no doubt about the efficacy of these tactics. Here is one example: in the 1984 elections, AIPAC helped defeat Senator Charles Percy from Illinois, who, according to a prominent Lobby figure, had ‘displayed insensitivity and even hostility to our concerns’. Thomas Dine, the head of AIPAC at the time, explained what happened: ‘All the Jews in America, from coast to coast, gathered to oust Percy. And the American politicians – those who hold public positions now, and those who aspire – got the message.’

AIPAC’s influence on Capitol Hill goes even further. According to Douglas Bloomfield, a former AIPAC staff member, ‘it is common for members of Congress and their staffs to turn to AIPAC first when they need information, before calling the Library of Congress, the Congressional Research Service, committee staff or administration experts.’ More important, he notes that AIPAC is ‘often called on to draft speeches, work on legislation, advise on tactics, perform research, collect co-sponsors and marshal votes’.

The bottom line is that AIPAC, a de facto agent for a foreign government, has a stranglehold on Congress, with the result that US policy towards Israel is not debated there, even though that policy has important consequences for the entire world. In other words, one of the three main branches of the government is firmly committed to supporting Israel. As one former Democratic senator, Ernest Hollings, noted on leaving office, ‘you can’t have an Israeli policy other than what AIPAC gives you around here.’ Or as Ariel Sharon once told an American audience, ‘when people ask me how they can help Israel, I tell them: “Help AIPAC.”’

Thanks in part to the influence Jewish voters have on presidential elections, the Lobby also has significant leverage over the executive branch. Although they make up fewer than 3 per cent of the population, they make large campaign donations to candidates from both parties. The Washington Post once estimated that Democratic presidential candidates ‘depend on Jewish supporters to supply as much as 60 per cent of the money’. And because Jewish voters have high turn-out rates and are concentrated in key states like California, Florida, Illinois, New York and Pennsylvania, presidential candidates go to great lengths not to antagonise them.

Key organisations in the Lobby make it their business to ensure that critics of Israel do not get important foreign policy jobs. Jimmy Carter wanted to make George Ball his first secretary of state, but knew that Ball was seen as critical of Israel and that the Lobby would oppose the appointment. In this way any aspiring policymaker is encouraged to become an overt supporter of Israel, which is why public critics of Israeli policy have become an endangered species in the foreign policy establishment.

When Howard Dean called for the United States to take a more ‘even-handed role’ in the Arab-Israeli conflict, Senator Joseph Lieberman accused him of selling Israel down the river and said his statement was ‘irresponsible’. Virtually all the top Democrats in the House signed a letter criticising Dean’s remarks, and the Chicago Jewish Star reported that ‘anonymous attackers … are clogging the email inboxes of Jewish leaders around the country, warning – without much evidence – that Dean would somehow be bad for Israel.’

This worry was absurd; Dean is in fact quite hawkish on Israel: his campaign co-chair was a former AIPAC president, and Dean said his own views on the Middle East more closely reflected those of AIPAC than those of the more moderate Americans for Peace Now. He had merely suggested that to ‘bring the sides together’, Washington should act as an honest broker. This is hardly a radical idea, but the Lobby doesn’t tolerate even-handedness.

During the Clinton administration, Middle Eastern policy was largely shaped by officials with close ties to Israel or to prominent pro-Israel organisations; among them, Martin Indyk, the former deputy director of research at AIPAC and co-founder of the pro-Israel Washington Institute for Near East Policy (WINEP); Dennis Ross, who joined WINEP after leaving government in 2001; and Aaron Miller, who has lived in Israel and often visits the country. These men were among Clinton’s closest advisers at the Camp David summit in July 2000. Although all three supported the Oslo peace process and favoured the creation of a Palestinian state, they did so only within the limits of what would be acceptable to Israel. The American delegation took its cues from Ehud Barak, co-ordinated its negotiating positions with Israel in advance, and did not offer independent proposals. Not surprisingly, Palestinian negotiators complained that they were ‘negotiating with two Israeli teams – one displaying an Israeli flag, and one an American flag’.

The situation is even more pronounced in the Bush administration, whose ranks have included such fervent advocates of the Israeli cause as Elliot Abrams, John Bolton, Douglas Feith, I. Lewis (‘Scooter’) Libby, Richard Perle, Paul Wolfowitz and David Wurmser. As we shall see, these officials have consistently pushed for policies favoured by Israel and backed by organisations in the Lobby.

The Lobby doesn’t want an open debate, of course, because that might lead Americans to question the level of support they provide. Accordingly, pro-Israel organisations work hard to influence the institutions that do most to shape popular opinion.

The Lobby’s perspective prevails in the mainstream media: the debate among Middle East pundits, the journalist Eric Alterman writes, is ‘dominated by people who cannot imagine criticising Israel’. He lists 61 ‘columnists and commentators who can be counted on to support Israel reflexively and without qualification’. Conversely, he found just five pundits who consistently criticise Israeli actions or endorse Arab positions. Newspapers occasionally publish guest op-eds challenging Israeli policy, but the balance of opinion clearly favours the other side. It is hard to imagine any mainstream media outlet in the United States publishing a piece like this one.

‘Shamir, Sharon, Bibi – whatever those guys want is pretty much fine by me,’ Robert Bartley once remarked. Not surprisingly, his newspaper, the Wall Street Journal, along with other prominent papers like the Chicago Sun-Times and the Washington Times, regularly runs editorials that strongly support Israel. Magazines like Commentary, the New Republic and the Weekly Standard defend Israel at every turn.

Editorial bias is also found in papers like the New York Times, which occasionally criticises Israeli policies and sometimes concedes that the Palestinians have legitimate grievances, but is not even-handed. In his memoirs the paper’s former executive editor Max Frankel acknowledges the impact his own attitude had on his editorial decisions: ‘I was much more deeply devoted to Israel than I dared to assert … Fortified by my knowledge of Israel and my friendships there, I myself wrote most of our Middle East commentaries. As more Arab than Jewish readers recognised, I wrote them from a pro-Israel perspective.’

News reports are more even-handed, in part because reporters strive to be objective, but also because it is difficult to cover events in the Occupied Territories without acknowledging Israel’s actions on the ground. To discourage unfavourable reporting, the Lobby organises letter-writing campaigns, demonstrations and boycotts of news outlets whose content it considers anti-Israel. One CNN executive has said that he sometimes gets 6000 email messages in a single day complaining about a story. In May 2003, the pro-Israel Committee for Accurate Middle East Reporting in America (CAMERA) organised demonstrations outside National Public Radio stations in 33 cities; it also tried to persuade contributors to withhold support from NPR until its Middle East coverage becomes more sympathetic to Israel. Boston’s NPR station, WBUR, reportedly lost more than $1 million in contributions as a result of these efforts. Further pressure on NPR has come from Israel’s friends in Congress, who have asked for an internal audit of its Middle East coverage as well as more oversight.

The Israeli side also dominates the think tanks which play an important role in shaping public debate as well as actual policy. The Lobby created its own think tank in 1985, when Martin Indyk helped to found WINEP. Although WINEP plays down its links to Israel, claiming instead to provide a ‘balanced and realistic’ perspective on Middle East issues, it is funded and run by individuals deeply committed to advancing Israel’s agenda.

The Lobby’s influence extends well beyond WINEP, however. Over the past 25 years, pro-Israel forces have established a commanding presence at the American Enterprise Institute, the Brookings Institution, the Center for Security Policy, the Foreign Policy Research Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the Hudson Institute, the Institute for Foreign Policy Analysis and the Jewish Institute for National Security Affairs (JINSA). These think tanks employ few, if any, critics of US support for Israel.

Take the Brookings Institution. For many years, its senior expert on the Middle East was William Quandt, a former NSC official with a well-deserved reputation for even-handedness. Today, Brookings’s coverage is conducted through the Saban Center for Middle East Studies, which is financed by Haim Saban, an Israeli-American businessman and ardent Zionist. The centre’s director is the ubiquitous Martin Indyk. What was once a non-partisan policy institute is now part of the pro-Israel chorus.

Where the Lobby has had the most difficulty is in stifling debate on university campuses. In the 1990s, when the Oslo peace process was underway, there was only mild criticism of Israel, but it grew stronger with Oslo’s collapse and Sharon’s access to power, becoming quite vociferous when the IDF reoccupied the West Bank in spring 2002 and employed massive force to subdue the second intifada.

The Lobby moved immediately to ‘take back the campuses’. New groups sprang up, like the Caravan for Democracy, which brought Israeli speakers to US colleges. Established groups like the Jewish Council for Public Affairs and Hillel joined in, and a new group, the Israel on Campus Coalition, was formed to co-ordinate the many bodies that now sought to put Israel’s case. Finally, AIPAC more than tripled its spending on programmes to monitor university activities and to train young advocates, in order to ‘vastly expand the number of students involved on campus … in the national pro-Israel effort’.

The Lobby also monitors what professors write and teach. In September 2002, Martin Kramer and Daniel Pipes, two passionately pro-Israel neo-conservatives, established a website (Campus Watch) that posted dossiers on suspect academics and encouraged students to report remarks or behaviour that might be considered hostile to Israel. This transparent attempt to blacklist and intimidate scholars provoked a harsh reaction and Pipes and Kramer later removed the dossiers, but the website still invites students to report ‘anti-Israel’ activity.

Groups within the Lobby put pressure on particular academics and universities. Columbia has been a frequent target, no doubt because of the presence of the late Edward Said on its faculty. ‘One can be sure that any public statement in support of the Palestinian people by the pre-eminent literary critic Edward Said will elicit hundreds of emails, letters and journalistic accounts that call on us to denounce Said and to either sanction or fire him,’ Jonathan Cole, its former provost, reported. When Columbia recruited the historian Rashid Khalidi from Chicago, the same thing happened. It was a problem Princeton also faced a few years later when it considered wooing Khalidi away from Columbia.

A classic illustration of the effort to police academia occurred towards the end of 2004, when the David Project produced a film alleging that faculty members of Columbia’s Middle East Studies programme were anti-semitic and were intimidating Jewish students who stood up for Israel. Columbia was hauled over the coals, but a faculty committee which was assigned to investigate the charges found no evidence of anti-semitism and the only incident possibly worth noting was that one professor had ‘responded heatedly’ to a student’s question. The committee also discovered that the academics in question had themselves been the target of an overt campaign of intimidation.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of all this is the efforts Jewish groups have made to push Congress into establishing mechanisms to monitor what professors say. If they manage to get this passed, universities judged to have an anti-Israel bias would be denied federal funding. Their efforts have not yet succeeded, but they are an indication of the importance placed on controlling debate.

A number of Jewish philanthropists have recently established Israel Studies programmes (in addition to the roughly 130 Jewish Studies programmes already in existence) so as to increase the number of Israel-friendly scholars on campus. In May 2003, NYU announced the establishment of the Taub Center for Israel Studies; similar programmes have been set up at Berkeley, Brandeis and Emory. Academic administrators emphasise their pedagogical value, but the truth is that they are intended in large part to promote Israel’s image. Fred Laffer, the head of the Taub Foundation, makes it clear that his foundation funded the NYU centre to help counter the ‘Arabic [sic] point of view’ that he thinks is prevalent in NYU’s Middle East programmes.

No discussion of the Lobby would be complete without an examination of one of its most powerful weapons: the charge of anti-semitism. Anyone who criticises Israel’s actions or argues that pro-Israel groups have significant influence over US Middle Eastern policy – an influence AIPAC celebrates – stands a good chance of being labelled an anti-semite. Indeed, anyone who merely claims that there is an Israel Lobby runs the risk of being charged with anti-semitism, even though the Israeli media refer to America’s ‘Jewish Lobby’. In other words, the Lobby first boasts of its influence and then attacks anyone who calls attention to it. It’s a very effective tactic: anti-semitism is something no one wants to be accused of.

Europeans have been more willing than Americans to criticise Israeli policy, which some people attribute to a resurgence of anti-semitism in Europe. We are ‘getting to a point’, the US ambassador to the EU said in early 2004, ‘where it is as bad as it was in the 1930s’. Measuring anti-semitism is a complicated matter, but the weight of evidence points in the opposite direction. In the spring of 2004, when accusations of European anti-semitism filled the air in America, separate surveys of European public opinion conducted by the US-based Anti-Defamation League and the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press found that it was in fact declining. In the 1930s, by contrast, anti-semitism was not only widespread among Europeans of all classes but considered quite acceptable.

The Lobby and its friends often portray France as the most anti-semitic country in Europe. But in 2003, the head of the French Jewish community said that ‘France is not more anti-semitic than America.’ According to a recent article in Ha’aretz, the French police have reported that anti-semitic incidents declined by almost 50 per cent in 2005; and this even though France has the largest Muslim population of any European country. Finally, when a French Jew was murdered in Paris last month by a Muslim gang, tens of thousands of demonstrators poured into the streets to condemn anti-semitism. Jacques Chirac and Dominique de Villepin both attended the victim’s memorial service to show their solidarity.

No one would deny that there is anti-semitism among European Muslims, some of it provoked by Israel’s conduct towards the Palestinians and some of it straightforwardly racist. But this is a separate matter with little bearing on whether or not Europe today is like Europe in the 1930s. Nor would anyone deny that there are still some virulent autochthonous anti-semites in Europe (as there are in the United States) but their numbers are small and their views are rejected by the vast majority of Europeans.

Israel’s advocates, when pressed to go beyond mere assertion, claim that there is a ‘new anti-semitism’, which they equate with criticism of Israel. In other words, criticise Israeli policy and you are by definition an anti-semite. When the synod of the Church of England recently voted to divest from Caterpillar Inc on the grounds that it manufactures the bulldozers used by the Israelis to demolish Palestinian homes, the Chief Rabbi complained that this would ‘have the most adverse repercussions on … Jewish-Christian relations in Britain’, while Rabbi Tony Bayfield, the head of the Reform movement, said: ‘There is a clear problem of anti-Zionist – verging on anti-semitic – attitudes emerging in the grass-roots, and even in the middle ranks of the Church.’ But the Church was guilty merely of protesting against Israeli government policy.

Critics are also accused of holding Israel to an unfair standard or questioning its right to exist. But these are bogus charges too. Western critics of Israel hardly ever question its right to exist: they question its behaviour towards the Palestinians, as do Israelis themselves. Nor is Israel being judged unfairly. Israeli treatment of the Palestinians elicits criticism because it is contrary to widely accepted notions of human rights, to international law and to the principle of national self-determination. And it is hardly the only state that has faced sharp criticism on these grounds.

In the autumn of 2001, and especially in the spring of 2002, the Bush administration tried to reduce anti-American sentiment in the Arab world and undermine support for terrorist groups like al-Qaida by halting Israel’s expansionist policies in the Occupied Territories and advocating the creation of a Palestinian state. Bush had very significant means of persuasion at his disposal. He could have threatened to reduce economic and diplomatic support for Israel, and the American people would almost certainly have supported him. A May 2003 poll reported that more than 60 per cent of Americans were willing to withhold aid if Israel resisted US pressure to settle the conflict, and that number rose to 70 per cent among the ‘politically active’. Indeed, 73 per cent said that the United States should not favour either side.

Yet the administration failed to change Israeli policy, and Washington ended up backing it. Over time, the administration also adopted Israel’s own justifications of its position, so that US rhetoric began to mimic Israeli rhetoric. By February 2003, a Washington Post headline summarised the situation: ‘Bush and Sharon Nearly Identical on Mideast Policy.’ The main reason for this switch was the Lobby.

The story begins in late September 2001, when Bush began urging Sharon to show restraint in the Occupied Territories. He also pressed him to allow Israel’s foreign minister, Shimon Peres, to meet with Yasser Arafat, even though he (Bush) was highly critical of Arafat’s leadership. Bush even said publicly that he supported the creation of a Palestinian state. Alarmed, Sharon accused him of trying ‘to appease the Arabs at our expense’, warning that Israel ‘will not be Czechoslovakia’.

Bush was reportedly furious at being compared to Chamberlain, and the White House press secretary called Sharon’s remarks ‘unacceptable’. Sharon offered a pro forma apology, but quickly joined forces with the Lobby to persuade the administration and the American people that the United States and Israel faced a common threat from terrorism. Israeli officials and Lobby representatives insisted that there was no real difference between Arafat and Osama bin Laden: the United States and Israel, they said, should isolate the Palestinians’ elected leader and have nothing to do with him.

The Lobby also went to work in Congress. On 16 November, 89 senators sent Bush a letter praising him for refusing to meet with Arafat, but also demanding that the US not restrain Israel from retaliating against the Palestinians; the administration, they wrote, must state publicly that it stood behind Israel. According to the New York Times, the letter ‘stemmed’ from a meeting two weeks before between ‘leaders of the American Jewish community and key senators’, adding that AIPAC was ‘particularly active in providing advice on the letter’.

By late November, relations between Tel Aviv and Washington had improved considerably. This was thanks in part to the Lobby’s efforts, but also to America’s initial victory in Afghanistan, which reduced the perceived need for Arab support in dealing with al-Qaida. Sharon visited the White House in early December and had a friendly meeting with Bush.

In April 2002 trouble erupted again, after the IDF launched Operation Defensive Shield and resumed control of virtually all the major Palestinian areas on the West Bank. Bush knew that Israel’s actions would damage America’s image in the Islamic world and undermine the war on terrorism, so he demanded that Sharon ‘halt the incursions and begin withdrawal’. He underscored this message two days later, saying he wanted Israel to ‘withdraw without delay’. On 7 April, Condoleezza Rice, then Bush’s national security adviser, told reporters: ‘“Without delay” means without delay. It means now.’ That same day Colin Powell set out for the Middle East to persuade all sides to stop fighting and start negotiating.

Israel and the Lobby swung into action. Pro-Israel officials in the vice-president’s office and the Pentagon, as well as neo-conservative pundits like Robert Kagan and William Kristol, put the heat on Powell. They even accused him of having ‘virtually obliterated the distinction between terrorists and those fighting terrorists’. Bush himself was being pressed by Jewish leaders and Christian evangelicals. Tom DeLay and Dick Armey were especially outspoken about the need to support Israel, and DeLay and the Senate minority leader, Trent Lott, visited the White House and warned Bush to back off.

The first sign that Bush was caving in came on 11 April – a week after he told Sharon to withdraw his forces – when the White House press secretary said that the president believed Sharon was ‘a man of peace’. Bush repeated this statement publicly on Powell’s return from his abortive mission, and told reporters that Sharon had responded satisfactorily to his call for a full and immediate withdrawal. Sharon had done no such thing, but Bush was no longer willing to make an issue of it.

Meanwhile, Congress was also moving to back Sharon. On 2 May, it overrode the administration’s objections and passed two resolutions reaffirming support for Israel. (The Senate vote was 94 to 2; the House of Representatives version passed 352 to 21.) Both resolutions held that the United States ‘stands in solidarity with Israel’ and that the two countries were, to quote the House resolution, ‘now engaged in a common struggle against terrorism’. The House version also condemned ‘the ongoing support and co-ordination of terror by Yasser Arafat’, who was portrayed as a central part of the terrorism problem. Both resolutions were drawn up with the help of the Lobby. A few days later, a bipartisan congressional delegation on a fact-finding mission to Israel stated that Sharon should resist US pressure to negotiate with Arafat. On 9 May, a House appropriations subcommittee met to consider giving Israel an extra $200 million to fight terrorism. Powell opposed the package, but the Lobby backed it and Powell lost.

In short, Sharon and the Lobby took on the president of the United States and triumphed. Hemi Shalev, a journalist on the Israeli newspaper Ma’ariv, reported that Sharon’s aides ‘could not hide their satisfaction in view of Powell’s failure. Sharon saw the whites of President Bush’s eyes, they bragged, and the president blinked first.’ But it was Israel’s champions in the United States, not Sharon or Israel, that played the key role in defeating Bush.

The situation has changed little since then. The Bush administration refused ever again to have dealings with Arafat. After his death, it embraced the new Palestinian leader, Mahmoud Abbas, but has done little to help him. Sharon continued to develop his plan to impose a unilateral settlement on the Palestinians, based on ‘disengagement’ from Gaza coupled with continued expansion on the West Bank. By refusing to negotiate with Abbas and making it impossible for him to deliver tangible benefits to the Palestinian people, Sharon’s strategy contributed directly to Hamas’s electoral victory. With Hamas in power, however, Israel has another excuse not to negotiate. The US administration has supported Sharon’s actions (and those of his successor, Ehud Olmert). Bush has even endorsed unilateral Israeli annexations in the Occupied Territories, reversing the stated policy of every president since Lyndon Johnson.

US officials have offered mild criticisms of a few Israeli actions, but have done little to help create a viable Palestinian state. Sharon has Bush ‘wrapped around his little finger’, the former national security adviser Brent Scowcroft said in October 2004. If Bush tries to distance the US from Israel, or even criticises Israeli actions in the Occupied Territories, he is certain to face the wrath of the Lobby and its supporters in Congress. Democratic presidential candidates understand that these are facts of life, which is the reason John Kerry went to great lengths to display unalloyed support for Israel in 2004, and why Hillary Clinton is doing the same thing today.

Maintaining US support for Israel’s policies against the Palestinians is essential as far as the Lobby is concerned, but its ambitions do not stop there. It also wants America to help Israel remain the dominant regional power. The Israeli government and pro-Israel groups in the United States have worked together to shape the administration’s policy towards Iraq, Syria and Iran, as well as its grand scheme for reordering the Middle East.

Pressure from Israel and the Lobby was not the only factor behind the decision to attack Iraq in March 2003, but it was critical. Some Americans believe that this was a war for oil, but there is hardly any direct evidence to support this claim. Instead, the war was motivated in good part by a desire to make Israel more secure. According to Philip Zelikow, a former member of the president’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, the executive director of the 9/11 Commission, and now a counsellor to Condoleezza Rice, the ‘real threat’ from Iraq was not a threat to the United States. The ‘unstated threat’ was the ‘threat against Israel’, Zelikow told an audience at the University of Virginia in September 2002. ‘The American government,’ he added, ‘doesn’t want to lean too hard on it rhetorically, because it is not a popular sell.’

On 16 August 2002, 11 days before Dick Cheney kicked off the campaign for war with a hardline speech to the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the Washington Post reported that ‘Israel is urging US officials not to delay a military strike against Iraq’s Saddam Hussein.’ By this point, according to Sharon, strategic co-ordination between Israel and the US had reached ‘unprecedented dimensions’, and Israeli intelligence officials had given Washington a variety of alarming reports about Iraq’s WMD programmes. As one retired Israeli general later put it, ‘Israeli intelligence was a full partner to the picture presented by American and British intelligence regarding Iraq’s non-conventional capabilities.’

Israeli leaders were deeply distressed when Bush decided to seek Security Council authorisation for war, and even more worried when Saddam agreed to let UN inspectors back in. ‘The campaign against Saddam Hussein is a must,’ Shimon Peres told reporters in September 2002. ‘Inspections and inspectors are good for decent people, but dishonest people can overcome easily inspections and inspectors.’

At the same time, Ehud Barak wrote a New York Times op-ed warning that ‘the greatest risk now lies in inaction.’ His predecessor as prime minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, published a similar piece in the Wall Street Journal, entitled: ‘The Case for Toppling Saddam’. ‘Today nothing less than dismantling his regime will do,’ he declared. ‘I believe I speak for the overwhelming majority of Israelis in supporting a pre-emptive strike against Saddam’s regime.’ Or as Ha’aretz reported in February 2003, ‘the military and political leadership yearns for war in Iraq.’

As Netanyahu suggested, however, the desire for war was not confined to Israel’s leaders. Apart from Kuwait, which Saddam invaded in 1990, Israel was the only country in the world where both politicians and public favoured war. As the journalist Gideon Levy observed at the time, ‘Israel is the only country in the West whose leaders support the war unreservedly and where no alternative opinion is voiced.’ In fact, Israelis were so gung-ho that their allies in America told them to damp down their rhetoric, or it would look as if the war would be fought on Israel’s behalf.

Within the US, the main driving force behind the war was a small band of neo-conservatives, many with ties to Likud. But leaders of the Lobby’s major organisations lent their voices to the campaign. ‘As President Bush attempted to sell the … war in Iraq,’ the Forward reported, ‘America’s most important Jewish organisations rallied as one to his defence. In statement after statement community leaders stressed the need to rid the world of Saddam Hussein and his weapons of mass destruction.’ The editorial goes on to say that ‘concern for Israel’s safety rightfully factored into the deliberations of the main Jewish groups.’

Although neo-conservatives and other Lobby leaders were eager to invade Iraq, the broader American Jewish community was not. Just after the war started, Samuel Freedman reported that ‘a compilation of nationwide opinion polls by the Pew Research Center shows that Jews are less supportive of the Iraq war than the population at large, 52 per cent to 62 per cent.’ Clearly, it would be wrong to blame the war in Iraq on ‘Jewish influence’. Rather, it was due in large part to the Lobby’s influence, especially that of the neo-conservatives within it.

The neo-conservatives had been determined to topple Saddam even before Bush became president. They caused a stir early in 1998 by publishing two open letters to Clinton, calling for Saddam’s removal from power. The signatories, many of whom had close ties to pro-Israel groups like JINSA or WINEP, and who included Elliot Abrams, John Bolton, Douglas Feith, William Kristol, Bernard Lewis, Donald Rumsfeld, Richard Perle and Paul Wolfowitz, had little trouble persuading the Clinton administration to adopt the general goal of ousting Saddam. But they were unable to sell a war to achieve that objective. They were no more able to generate enthusiasm for invading Iraq in the early months of the Bush administration. They needed help to achieve their aim. That help arrived with 9/11. Specifically, the events of that day led Bush and Cheney to reverse course and become strong proponents of a preventive war.

At a key meeting with Bush at Camp David on 15 September, Wolfowitz advocated attacking Iraq before Afghanistan, even though there was no evidence that Saddam was involved in the attacks on the US and bin Laden was known to be in Afghanistan. Bush rejected his advice and chose to go after Afghanistan instead, but war with Iraq was now regarded as a serious possibility and on 21 November the president charged military planners with developing concrete plans for an invasion.

Other neo-conservatives were meanwhile at work in the corridors of power. We don’t have the full story yet, but scholars like Bernard Lewis of Princeton and Fouad Ajami of Johns Hopkins reportedly played important roles in persuading Cheney that war was the best option, though neo-conservatives on his staff – Eric Edelman, John Hannah and Scooter Libby, Cheney’s chief of staff and one of the most powerful individuals in the administration – also played their part. By early 2002 Cheney had persuaded Bush; and with Bush and Cheney on board, war was inevitable.

Outside the administration, neo-conservative pundits lost no time in making the case that invading Iraq was essential to winning the war on terrorism. Their efforts were designed partly to keep up the pressure on Bush, and partly to overcome opposition to the war inside and outside the government. On 20 September, a group of prominent neo-conservatives and their allies published another open letter: ‘Even if evidence does not link Iraq directly to the attack,’ it read, ‘any strategy aiming at the eradication of terrorism and its sponsors must include a determined effort to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq.’ The letter also reminded Bush that ‘Israel has been and remains America’s staunchest ally against international terrorism.’ In the 1 October issue of the Weekly Standard, Robert Kagan and William Kristol called for regime change in Iraq as soon as the Taliban was defeated. That same day, Charles Krauthammer argued in the Washington Post that after the US was done with Afghanistan, Syria should be next, followed by Iran and Iraq: ‘The war on terrorism will conclude in Baghdad,’ when we finish off ‘the most dangerous terrorist regime in the world’.

This was the beginning of an unrelenting public relations campaign to win support for an invasion of Iraq, a crucial part of which was the manipulation of intelligence in such a way as to make it seem as if Saddam posed an imminent threat. For example, Libby pressured CIA analysts to find evidence supporting the case for war and helped prepare Colin Powell’s now discredited briefing to the UN Security Council. Within the Pentagon, the Policy Counterterrorism Evaluation Group was charged with finding links between al-Qaida and Iraq that the intelligence community had supposedly missed. Its two key members were David Wurmser, a hard-core neo-conservative, and Michael Maloof, a Lebanese-American with close ties to Perle. Another Pentagon group, the so-called Office of Special Plans, was given the task of uncovering evidence that could be used to sell the war. It was headed by Abram Shulsky, a neo-conservative with long-standing ties to Wolfowitz, and its ranks included recruits from pro-Israel think tanks. Both these organisations were created after 9/11 and reported directly to Douglas Feith.

Like virtually all the neo-conservatives, Feith is deeply committed to Israel; he also has long-term ties to Likud. He wrote articles in the 1990s supporting the settlements and arguing that Israel should retain the Occupied Territories. More important, along with Perle and Wurmser, he wrote the famous ‘Clean Break’ report in June 1996 for Netanyahu, who had just become prime minister. Among other things, it recommended that Netanyahu ‘focus on removing Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq – an important Israeli strategic objective in its own right’. It also called for Israel to take steps to reorder the entire Middle East. Netanyahu did not follow their advice, but Feith, Perle and Wurmser were soon urging the Bush administration to pursue those same goals. The Ha’aretz columnist Akiva Eldar warned that Feith and Perle ‘are walking a fine line between their loyalty to American governments … and Israeli interests’.

Wolfowitz is equally committed to Israel. The Forward once described him as ‘the most hawkishly pro-Israel voice in the administration’, and selected him in 2002 as first among 50 notables who ‘have consciously pursued Jewish activism’. At about the same time, JINSA gave Wolfowitz its Henry M. Jackson Distinguished Service Award for promoting a strong partnership between Israel and the United States; and the Jerusalem Post, describing him as ‘devoutly pro-Israel’, named him ‘Man of the Year’ in 2003.

Finally, a brief word is in order about the neo-conservatives’ prewar support of Ahmed Chalabi, the unscrupulous Iraqi exile who headed the Iraqi National Congress. They backed Chalabi because he had established close ties with Jewish-American groups and had pledged to foster good relations with Israel once he gained power. This was precisely what pro-Israel proponents of regime change wanted to hear. Matthew Berger laid out the essence of the bargain in the Jewish Journal: ‘The INC saw improved relations as a way to tap Jewish influence in Washington and Jerusalem and to drum up increased support for its cause. For their part, the Jewish groups saw an opportunity to pave the way for better relations between Israel and Iraq, if and when the INC is involved in replacing Saddam Hussein’s regime.’

Given the neo-conservatives’ devotion to Israel, their obsession with Iraq, and their influence in the Bush administration, it isn’t surprising that many Americans suspected that the war was designed to further Israeli interests. Last March, Barry Jacobs of the American Jewish Committee acknowledged that the belief that Israel and the neo-conservatives had conspired to get the US into a war in Iraq was ‘pervasive’ in the intelligence community. Yet few people would say so publicly, and most of those who did – including Senator Ernest Hollings and Representative James Moran – were condemned for raising the issue. Michael Kinsley wrote in late 2002 that ‘the lack of public discussion about the role of Israel … is the proverbial elephant in the room.’ The reason for the reluctance to talk about it, he observed, was fear of being labelled an anti-semite. There is little doubt that Israel and the Lobby were key factors in the decision to go to war. It’s a decision the US would have been far less likely to take without their efforts. And the war itself was intended to be only the first step. A front-page headline in the Wall Street Journal shortly after the war began says it all: ‘President’s Dream: Changing Not Just Regime but a Region: A Pro-US, Democratic Area Is a Goal that Has Israeli and Neo-Conservative Roots.’

Pro-Israel forces have long been interested in getting the US military more directly involved in the Middle East. But they had limited success during the Cold War, because America acted as an ‘off-shore balancer’ in the region. Most forces designated for the Middle East, like the Rapid Deployment Force, were kept ‘over the horizon’ and out of harm’s way. The idea was to play local powers off against each other – which is why the Reagan administration supported Saddam against revolutionary Iran during the Iran-Iraq War – in order to maintain a balance favourable to the US.

This policy changed after the first Gulf War, when the Clinton administration adopted a strategy of ‘dual containment’. Substantial US forces would be stationed in the region in order to contain both Iran and Iraq, instead of one being used to check the other. The father of dual containment was none other than Martin Indyk, who first outlined the strategy in May 1993 at WINEP and then implemented it as director for Near East and South Asian Affairs at the National Security Council.

By the mid-1990s there was considerable dissatisfaction with dual containment, because it made the United States the mortal enemy of two countries that hated each other, and forced Washington to bear the burden of containing both. But it was a strategy the Lobby favoured and worked actively in Congress to preserve. Pressed by AIPAC and other pro-Israel forces, Clinton toughened up the policy in the spring of 1995 by imposing an economic embargo on Iran. But AIPAC and the others wanted more. The result was the 1996 Iran and Libya Sanctions Act, which imposed sanctions on any foreign companies investing more than $40 million to develop petroleum resources in Iran or Libya. As Ze’ev Schiff, the military correspondent of Ha’aretz, noted at the time, ‘Israel is but a tiny element in the big scheme, but one should not conclude that it cannot influence those within the Beltway.’

By the late 1990s, however, the neo-conservatives were arguing that dual containment was not enough and that regime change in Iraq was essential. By toppling Saddam and turning Iraq into a vibrant democracy, they argued, the US would trigger a far-reaching process of change throughout the Middle East. The same line of thinking was evident in the ‘Clean Break’ study the neo-conservatives wrote for Netanyahu. By 2002, when an invasion of Iraq was on the front-burner, regional transformation was an article of faith in neo-conservative circles.

Charles Krauthammer describes this grand scheme as the brainchild of Natan Sharansky, but Israelis across the political spectrum believed that toppling Saddam would alter the Middle East to Israel’s advantage. Aluf Benn reported in Ha’aretz (17 February 2003):

Senior IDF officers and those close to Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, such as National Security Adviser Ephraim Halevy, paint a rosy picture of the wonderful future Israel can expect after the war. They envision a domino effect, with the fall of Saddam Hussein followed by that of Israel’s other enemies … Along with these leaders will disappear terror and weapons of mass destruction.

Once Baghdad fell in mid-April 2003, Sharon and his lieutenants began urging Washington to target Damascus. On 16 April, Sharon, interviewed in Yedioth Ahronoth, called for the United States to put ‘very heavy’ pressure on Syria, while Shaul Mofaz, his defence minister, interviewed in Ma’ariv, said: ‘We have a long list of issues that we are thinking of demanding of the Syrians and it is appropriate that it should be done through the Americans.’ Ephraim Halevy told a WINEP audience that it was now important for the US to get rough with Syria, and the Washington Post reported that Israel was ‘fuelling the campaign’ against Syria by feeding the US intelligence reports about the actions of Bashar Assad, the Syrian president.

Prominent members of the Lobby made the same arguments. Wolfowitz declared that ‘there has got to be regime change in Syria,’ and Richard Perle told a journalist that ‘a short message, a two-worded message’ could be delivered to other hostile regimes in the Middle East: ‘You’re next.’ In early April, WINEP released a bipartisan report stating that Syria ‘should not miss the message that countries that pursue Saddam’s reckless, irresponsible and defiant behaviour could end up sharing his fate’. On 15 April, Yossi Klein Halevi wrote a piece in the Los Angeles Times entitled ‘Next, Turn the Screws on Syria’, while the following day Zev Chafets wrote an article for the New York Daily News entitled ‘Terror-Friendly Syria Needs a Change, Too’. Not to be outdone, Lawrence Kaplan wrote in the New Republic on 21 April that Assad was a serious threat to America.

Back on Capitol Hill, Congressman Eliot Engel had reintroduced the Syria Accountability and Lebanese Sovereignty Restoration Act. It threatened sanctions against Syria if it did not withdraw from Lebanon, give up its WMD and stop supporting terrorism, and it also called for Syria and Lebanon to take concrete steps to make peace with Israel. This legislation was strongly endorsed by the Lobby – by AIPAC especially – and ‘framed’, according to the Jewish Telegraph Agency, ‘by some of Israel’s best friends in Congress’. The Bush administration had little enthusiasm for it, but the anti-Syrian act passed overwhelmingly (398 to 4 in the House; 89 to 4 in the Senate), and Bush signed it into law on 12 December 2003.

The administration itself was still divided about the wisdom of targeting Syria. Although the neo-conservatives were eager to pick a fight with Damascus, the CIA and the State Department were opposed to the idea. And even after Bush signed the new law, he emphasised that he would go slowly in implementing it. His ambivalence is understandable. First, the Syrian government had not only been providing important intelligence about al-Qaida since 9/11: it had also warned Washington about a planned terrorist attack in the Gulf and given CIA interrogators access to Mohammed Zammar, the alleged recruiter of some of the 9/11 hijackers. Targeting the Assad regime would jeopardise these valuable connections, and thereby undermine the larger war on terrorism.

Second, Syria had not been on bad terms with Washington before the Iraq war (it had even voted for UN Resolution 1441), and was itself no threat to the United States. Playing hardball with it would make the US look like a bully with an insatiable appetite for beating up Arab states. Third, putting Syria on the hit list would give Damascus a powerful incentive to cause trouble in Iraq. Even if one wanted to bring pressure to bear, it made good sense to finish the job in Iraq first. Yet Congress insisted on putting the screws on Damascus, largely in response to pressure from Israeli officials and groups like AIPAC. If there were no Lobby, there would have been no Syria Accountability Act, and US policy towards Damascus would have been more in line with the national interest.

Israelis tend to describe every threat in the starkest terms, but Iran is widely seen as their most dangerous enemy because it is the most likely to acquire nuclear weapons. Virtually all Israelis regard an Islamic country in the Middle East with nuclear weapons as a threat to their existence. ‘Iraq is a problem … But you should understand, if you ask me, today Iran is more dangerous than Iraq,’ the defence minister, Binyamin Ben-Eliezer, remarked a month before the Iraq war.

Sharon began pushing the US to confront Iran in November 2002, in an interview in the Times. Describing Iran as the ‘centre of world terror’, and bent on acquiring nuclear weapons, he declared that the Bush administration should put the strong arm on Iran ‘the day after’ it conquered Iraq. In late April 2003, Ha’aretz reported that the Israeli ambassador in Washington was calling for regime change in Iran. The overthrow of Saddam, he noted, was ‘not enough’. In his words, America ‘has to follow through. We still have great threats of that magnitude coming from Syria, coming from Iran.’

The neo-conservatives, too, lost no time in making the case for regime change in Tehran. On 6 May, the AEI co-sponsored an all-day conference on Iran with the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies and the Hudson Institute, both champions of Israel. The speakers were all strongly pro-Israel, and many called for the US to replace the Iranian regime with a democracy. As usual, a bevy of articles by prominent neo-conservatives made the case for going after Iran. ‘The liberation of Iraq was the first great battle for the future of the Middle East … But the next great battle – not, we hope, a military battle – will be for Iran,’ William Kristol wrote in the Weekly Standard on 12 May.

The administration has responded to the Lobby’s pressure by working overtime to shut down Iran’s nuclear programme. But Washington has had little success, and Iran seems determined to create a nuclear arsenal. As a result, the Lobby has intensified its pressure. Op-eds and other articles now warn of imminent dangers from a nuclear Iran, caution against any appeasement of a ‘terrorist’ regime, and hint darkly of preventive action should diplomacy fail. The Lobby is pushing Congress to approve the Iran Freedom Support Act, which would expand existing sanctions. Israeli officials also warn they may take pre-emptive action should Iran continue down the nuclear road, threats partly intended to keep Washington’s attention on the issue.

One might argue that Israel and the Lobby have not had much influence on policy towards Iran, because the US has its own reasons for keeping Iran from going nuclear. There is some truth in this, but Iran’s nuclear ambitions do not pose a direct threat to the US. If Washington could live with a nuclear Soviet Union, a nuclear China or even a nuclear North Korea, it can live with a nuclear Iran. And that is why the Lobby must keep up constant pressure on politicians to confront Tehran. Iran and the US would hardly be allies if the Lobby did not exist, but US policy would be more temperate and preventive war would not be a serious option.

It is not surprising that Israel and its American supporters want the US to deal with any and all threats to Israel’s security. If their efforts to shape US policy succeed, Israel’s enemies will be weakened or overthrown, Israel will get a free hand with the Palestinians, and the US will do most of the fighting, dying, rebuilding and paying. But even if the US fails to transform the Middle East and finds itself in conflict with an increasingly radicalised Arab and Islamic world, Israel will end up protected by the world’s only superpower. This is not a perfect outcome from the Lobby’s point of view, but it is obviously preferable to Washington distancing itself, or using its leverage to force Israel to make peace with the Palestinians.

Can the Lobby’s power be curtailed? One would like to think so, given the Iraq debacle, the obvious need to rebuild America’s image in the Arab and Islamic world, and the recent revelations about AIPAC officials passing US government secrets to Israel. One might also think that Arafat’s death and the election of the more moderate Mahmoud Abbas would cause Washington to press vigorously and even-handedly for a peace agreement. In short, there are ample grounds for leaders to distance themselves from the Lobby and adopt a Middle East policy more consistent with broader US interests. In particular, using American power to achieve a just peace between Israel and the Palestinians would help advance the cause of democracy in the region.

But that is not going to happen – not soon anyway. AIPAC and its allies (including Christian Zionists) have no serious opponents in the lobbying world. They know it has become more difficult to make Israel’s case today, and they are responding by taking on staff and expanding their activities. Besides, American politicians remain acutely sensitive to campaign contributions and other forms of political pressure, and major media outlets are likely to remain sympathetic to Israel no matter what it does.

The Lobby’s influence causes trouble on several fronts. It increases the terrorist danger that all states face – including America’s European allies. It has made it impossible to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a situation that gives extremists a powerful recruiting tool, increases the pool of potential terrorists and sympathisers, and contributes to Islamic radicalism in Europe and Asia.

Equally worrying, the Lobby’s campaign for regime change in Iran and Syria could lead the US to attack those countries, with potentially disastrous effects. We don’t need another Iraq. At a minimum, the Lobby’s hostility towards Syria and Iran makes it almost impossible for Washington to enlist them in the struggle against al-Qaida and the Iraqi insurgency, where their help is badly needed.

There is a moral dimension here as well. Thanks to the Lobby, the United States has become the de facto enabler of Israeli expansion in the Occupied Territories, making it complicit in the crimes perpetrated against the Palestinians. This situation undercuts Washington’s efforts to promote democracy abroad and makes it look hypocritical when it presses other states to respect human rights. US efforts to limit nuclear proliferation appear equally hypocritical given its willingness to accept Israel’s nuclear arsenal, which only encourages Iran and others to seek a similar capability.

Besides, the Lobby’s campaign to quash debate about Israel is unhealthy for democracy. Silencing sceptics by organising blacklists and boycotts – or by suggesting that critics are anti-semites – violates the principle of open debate on which democracy depends. The inability of Congress to conduct a genuine debate on these important issues paralyses the entire process of democratic deliberation. Israel’s backers should be free to make their case and to challenge those who disagree with them, but efforts to stifle debate by intimidation must be roundly condemned.

Finally, the Lobby’s influence has been bad for Israel. Its ability to persuade Washington to support an expansionist agenda has discouraged Israel from seizing opportunities – including a peace treaty with Syria and a prompt and full implementation of the Oslo Accords – that would have saved Israeli lives and shrunk the ranks of Palestinian extremists. Denying the Palestinians their legitimate political rights certainly has not made Israel more secure, and the long campaign to kill or marginalise a generation of Palestinian leaders has empowered extremist groups like Hamas, and reduced the number of Palestinian leaders who would be willing to accept a fair settlement and able to make it work. Israel itself would probably be better off if the Lobby were less powerful and US policy more even-handed.

There is a ray of hope, however. Although the Lobby remains a powerful force, the adverse effects of its influence are increasingly difficult to hide. Powerful states can maintain flawed policies for quite some time, but reality cannot be ignored for ever. What is needed is a candid discussion of the Lobby’s influence and a more open debate about US interests in this vital region. Israel’s well-being is one of those interests, but its continued occupation of the West Bank and its broader regional agenda are not. Open debate will expose the limits of the strategic and moral case for one-sided US support and could move the US to a position more consistent with its own national interest, with the interests of the other states in the region, and with Israel’s long-term interests as well.

10 March

An unedited version of this article is available at http://ksgnotes1.harvard.edu/Research/wpaper.nsf/rwp/RWP06-011, or at http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=891198.

On the LRB Blog: Taking Sides

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.